Fine tuning office design to our most fundamental needs

The best workplaces are always focused on people. Which is why many of the great pioneers of workplace thinking are from the social sciences, including disciplines such as psychology, ethnography and anthropology. These are the people who have shared the insights that help us to understand the characteristics of great office design.

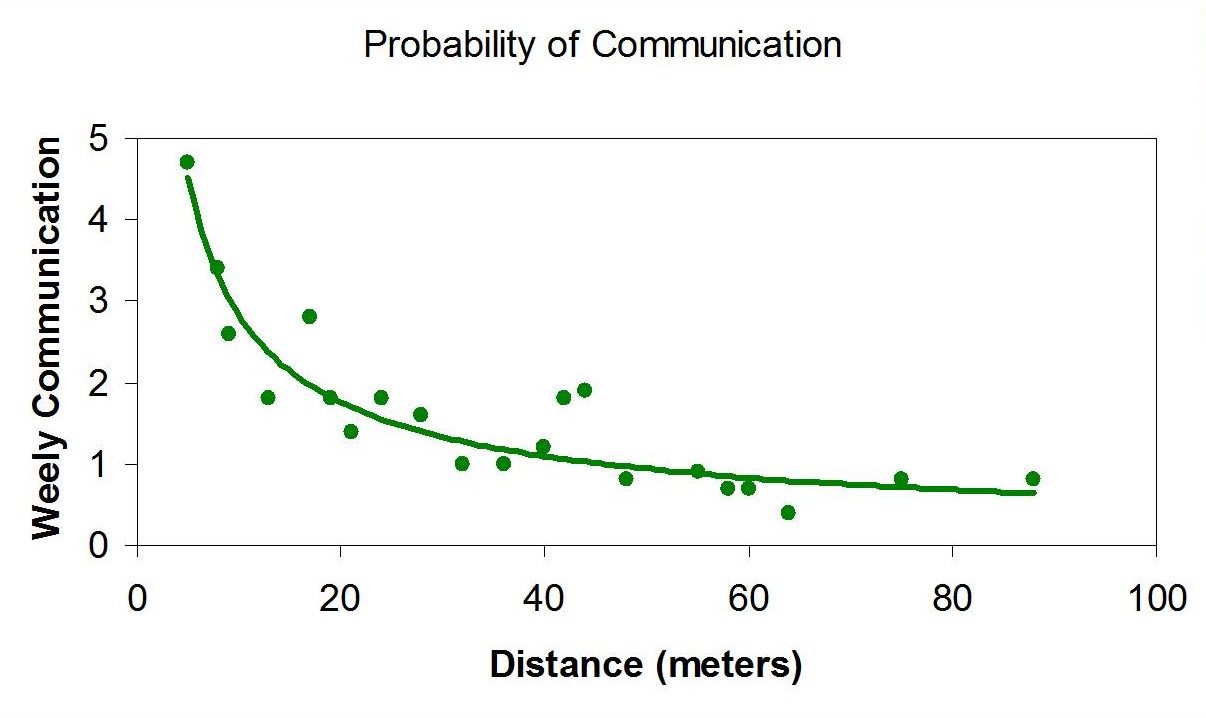

In particular, this relies on an awareness of the ways in which people interact in particular spaces. And one long-established body of research by the organisational psychologist Tom Allen at MIT describes the correlation between physical proximity and the frequency and value of communication between colleagues. In other words, a business case for the existence of offices in a world in which technology has made total remote working possible.

The architecture of innovation

In 1984, Allen published a book called Managing the Flow of Technology which first described what we now know as the Allen Curve. It graphed the powerful correlation between physical distance and the frequency of communication between colleagues.

In 1984, Allen published a book called Managing the Flow of Technology which first described what we now know as the Allen Curve. It graphed the powerful correlation between physical distance and the frequency of communication between colleagues.

So precisely was this defined in Allen’s research, that he found that 50 metres marks a cut-off point for the regular exchange of certain types of technical information between the engineers he studied. The distance between the engineers’ desks and offices had a significant impact on the frequency of communication between them.

It is a subject Allen has returned to repeatedly in the years since. In 2006, he published a book called The Organization and Architecture of Innovation co-authored with the German architect Gunter Henn. The book explores how physical space, networks, flows of information and organisational structure must be integrated to drive innovation.

The authors argue that: “rather than finding that the probability of telephone communication increases with distances, as face to face probability decays, our data shows a decay in the use of all communication media with distance. We do not keep separate sets of people, some of which we communicate in one medium and some by another. The more often we see someone face to face, the more likely it is that we will telephone the person or communicate in some other medium.”

The social life of space

The issue of how people interact with each other was also the subject of an earlier study by the anthropologist William H Whyte who, in 1970, established a research project that applied anthropological principles to the study of how people used space and interacted with each other in the streets and parks of New York.

The findings of what he referred to as The Street Life Project were published in a book called The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces and a film, summarised here. One interesting excerpt from the film looks at the way people use seating in shared spaces to create their own best space. We take something like a moveable chair for granted, but the film refers to its as a ‘wonderful invention’.

The narrator draws attention to the rituals we perform when we claim a chair as our own, including a small, often pointless but nonetheless crucial relocation of the chair. The film highlights how important it is to empower people to choose the location of the chair, even when it becomes apparent that it was in the best location to begin with.

Whyte’s film also talks about the relationship between seating arrangements and circulation space. He is describing an urban setting, but the same thinking is appropriate for office design because both are about facilitating the better lives and interactions of people. He explores the way people respond to light levels and our attraction to stimulating spaces.

The film describes how our ritualistic behaviours play out in such spaces, how we respond to chance encounters, the three phases of a goodbye and the way we mirror each other’s speech and gestures as a way of establishing rapport.

An aware of the psychological and anthropological research into the way we use space and interact is essential when it comes to creating both great workplaces and great products to use in them. Such seemingly disparate disciplines allow designers and occupiers to address and harness the complexities of personal behaviour and organisational culture to create great places to work. We might take something like a moveable chair for granted but it’s also worth reminding ourselves what a ‘wonderful invention’ it is when it is fine tuned to our most fundamental needs.